<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

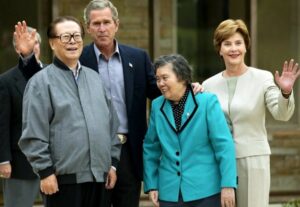

In February 2002, President George W. Bush visited Beijing and met with President Jiang Zemin. Their discussions covered the world’s hotspots, with a special focus on events in Iraq and North Korea. President Bush, in an unscripted moment, thanked President Jiang for the releases of Hong Kong resident and bible smuggler Li Guangqiang and the Tibetan musicologist Ngawang Choephel. Bush also invited Jiang to make a working visit to the United States in October, on his way to the APEC Summit in Mexico City. Perhaps they might meet at his famous ranch in Crawford, Texas. Jiang happily accepted the invitation.

The group advising Jiang on which prisoners to release was convened. There were a number of good candidates for early release, including, first off, school teacher Jigme Sangpo, but also Democracy Party Chairman Xu Wenli and Uyghur businesswoman Rebiya Kadeer. There was no shortage of others worthy of clemency.

Jigme Sangpo was released on March 31, 2002, six weeks after the Bush-Jiang summit. He flew to the United States on July 13, a month after I had visited him in Lhasa.

I left on a tour of European capitals in late August 2002, being received at senior levels by governments in London, Oslo, Stockholm, Copenhagen, and Geneva. My last stop was Bern. I arrived at around 10 AM on September 11, the first anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. I checked into the Savoy Hotel in the Old City and, at 11 AM, walked the short distance to the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs where I was received by Ambassador Peter Maurer, head of Political Section IV. We had a working lunch of traditional Swiss cuisine at a nearby restaurant. (Maurer went on to become Switzerland’s first ambassador to the United Nations. He is now the President of the International Committee of the Red Cross, based in Geneva.

A Divination in Lhasa

During the lunch, Ambassador Maurer asked me if I would be willing to meet a prominent Tibetan living in Switzerland by the name of Tsultim Tersey that evening. I said fine, and around 6 PM Mr. Tersey and his daughter showed up at my hotel. They gave me a special khata, a ceremonial Tibetan scarf, and we went out to find a restaurant. It was a cold and wet night. We found a quiet place.

As soon as we sat down, Tsultim Tersey pulled out a thick sheath of paper. It was a petition signed by 300 Tibetan Swiss citizens asking that I seek the release from prison of Ngawang Sangdrol, the young leader of a group known as the Singing Nuns of Drapchi. At the age of thirteen, Ngawang Sangdrol was detained and subsequently sentenced to three years in prison for counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement in November 1992. In October 1993, she and 13 other nuns secretly recorded 27 songs of devotion to their homeland and the Dalai Lama. The cassette recording was smuggled out of prison; it circulated widely among Tibetans in Tibet and overseas. For this act, the nuns had their sentences extended. Maintaining a spirit of defiance, Ngawang Sangdrol had her sentence extended again in 1996 and 1998. What had been a three-year sentence became a 23-year sentence. Her plight received the attention of many governments and friends of Tibet overseas, especially in Switzerland which is home to a large ethnic Tibetan population.

I accepted the petition and said that I would do what I could to press for her release, but that there were no guarantees that I would succeed. Tsultim Tersey replied: “You will succeed, you must succeed.”

He told me that, after Jigme Sangpo’s release, he traveled to Lhasa and met with the elderly former prisoner at his niece’s residence. While in Lhasa, Tersey also met with Tibetan officials and asked them to release Ngawang Sangdrol. He felt he was making progress, but at his last meeting with the officials he was told that Ngawang Sangdrol would not be released. He was very upset, and sought the advice of a shaman.

He asked the shaman if his effort to secure the release of Ngawang Sangdrol would eventually succeed. The shaman performed a divination. The answer was no. He then asked the shaman whether an American businessman by the name of John Kamm would succeed. The shaman once again performed a divination. The answer: “She will be released within six months.”

Tsultim Tersey then told me that a kind and generous couple who lived in Geneva, Mrs. Maria José Rossotto and Professor Paolo Rossotto, had a strong interest in Tibet and in the Ngawang Sangdrol case in particular, and that if I needed their help I should contact them.

I left the next day for Hong Kong. On the flight I decided to concentrate my efforts on securing the release of Tibetans convicted of counterrevolutionary crimes who were still serving their sentences. Upon my arrival in Hong Kong I briefed American officials and made calls to Beijing. On September 23, I spoke to my principal interlocutor with whom I had worked on the Jigme Sangpo case. He told me that progress was being made on the cases of Xu Wenli and Rebiya Kadeer. There was no mention of Ngawang Sangdrol.

By that time, I had learned from other contacts in Beijing that Jiang Zemin, whose trip to Crawford was a month away, wanted to have a very special visit. He would be the fourth foreign leader to visit Crawford (Vladimir Putin of Russia, Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, and Prime Minister Tony Blair had all spent time with President Bush at his ranch). President Jiang would be the first Asian leader to be accorded this honor, and he wanted it to be memorable.

I called Lorne Craner, who was then Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of Democracy, Rights, and Labor at the State Department. Without detracting from the importance of securing the release of Xu Wenli and Rebiya Kadeer, I lobbied to include the release of Ngawang Sangdrol on the list of “deliverables” for the Jiang visit to Texas. Craner bought in.

Shortly after, I flew to Beijing where I met with my principal interlocutor. As tea was being served, he looked at me and said. “There’s a prisoner you’ve asked about. I have some news, but I can’t recall the prisoner’s name.” His colleague reminded him: “Ngawang.” I jumped in. “Ngawang Sangdrol?” My interlocutor replied “Yes, she can be released. We have discussed her case, and senior leaders were surprised to learn that someone so young has been serving such a long sentence.” We agreed to hold a three-way meeting the next day: I could make my pitch directly to the Prison Administration Bureau of the Ministry of Justice, with my interlocutor present.

The pitch went well and the following day, October 10, I had a wrap-up meeting with my principal interlocutor’s deputy. I was told that Ngawang Sangdrol would be released before the end of October. As in the case of Jigme Sangpo, I could travel to Lhasa at a future date, meet with Ngawang Sangdrol, and determine for myself if she wanted to leave China for medical treatment.

I left Beijing and flew home to San Francisco. Following back and forth calls with Beijing and Washington, I was called by my principal interlocutor’s deputy at 10 PM on October 16, San Francisco time, and told that Ngawang Sangdrol had just been released and that she was on her way to her sister’s home in Lhasa. I was told that I could release a statement to the press. I demurred. I wanted to be sure that she arrived safely at her sister’s home before announcing the news. Finally, at 1:30 AM on October 17, I got the call. Ngawang Sangdrol was safe at her sister’s home.

To Lhasa for Ngawang Sangdrol

In November and December, I struggled to fix a date for my visit to Beijing and Lhasa. In a letter to my principal interlocutor’s deputy faxed on December 30, I suggested dates in January 2003. I was told my visit was inconvenient in January. Opposition to letting Ngawang Sangdrol leave Lhasa had grown, and local officials did not want to see me. I surmised that, with Jiang Zemin having stepped down as Communist Party Secretary in November 2002, and with his successor Hu Jintao opposed to releasing prisoners for favors, prospects looked bleak. I pressed on, arguing that a promise is a promise, and that since Jiang Zemin would stay on as president of China, the capacity in which he had visited George Bush, until March 2003, surely he would approve my trip.

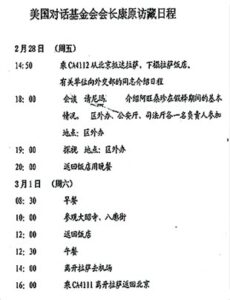

I tried again on January 21, suggesting dates of February 27 to March 5 for my visit to Beijing and Lhasa. This time I got the green light. After meetings in Washington with Lorne Craner and his colleagues in the Bureau of Democracy, Rights, and Labor and Mike Meserve, deputy director of the Office of Chinese and Mongolian Affairs in the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, I returned to San Francisco where I drafted and mailed a letter to Losang Geleg, deputy director of the Prison Administration Bureau of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). Attached to the letter was a list of 30 Tibetan political prisoners.

I had met Losang Geleg on my visit to Lhasa in June 2002. Like other foreigners who had met him, I was struck by this man’s openness and willingness to share information on prisoners. (In an article published by the official Xinhua news agency on January 21, 2003, Losang Geleg stated that there were 2,300 prisoners in Tibet, of whom “less than five percent” were serving sentences for crimes of counterrevolution and endangering state security.) In the letter I asked for clemency for three Tibetan prisoners serving sentences for counterrevolution: Phuntsog Nyidron, Jampel Changchub, and Ngawang Oezer. Phuntsog Nyidron was, like Ngawang Sangdrol, a “Singing Nun of Drapchi.” The other two prisoners were serving long sentences, passed down in 1989, for counterrevolutionary crimes (they had translated the Universal Declaration of Human Rights into Tibetan and had attempted to popularize it). Because the prison bureau was no longer responsible for Ngawang Sangdrol, I did not bring up her name, nor did I mention my imminent visit to Lhasa, in the letter to Losang Geleg.

I flew to Beijing on February 26, arriving on February 27. I departed Beijing for Lhasa via Chengdu on CA4112 on February 28, 2003. The night before I had dined with my principal interlocutor at the residence of American Ambassador Clark Randt. I was told that, despite opposition, my visit to Lhasa would go ahead as planned. I would be accompanied by a middle-ranking Ministry of Foreign Affairs official. I was asked not to say anything to anybody in Lhasa about a possible trip to the United States by Ngawang Sangdrol.

It was a smooth flight, notwithstanding a brawl involving angry Sichuanese in the seats right behind me. Too much baijiu, too early. The crew moved in quickly, and the plane, which was rocking in mid-air, stabilized.

Ngawang Sangdrol and her Niece

I arrived with my companion at Lhasa Airport at 4:00 PM on February 28. Unlike what happened when I had flown to Tibet’s capital in June 2002 for Jigme Sangpo, we were met at the appropriate level – a deputy director of the TAR Foreign Affairs Office greeted us. We were driven to the hotel, where we dropped off our bags, and taken to the FAO office in downtown Lhasa. This was to be a lightning visit; I would leave Lhasa the next day, 24 hours after I had arrived.

The meeting began at 6 PM. Officials on the TAR side included senior officials of the TAR foreign affairs and police organizations involved in the Ngawang Sangdrol case. I was pleasantly surprised to see Losang Geleg seated at the table. He agreed to see me for a few minutes after the meeting.

Nima Tsering of the TAR Public Security Bureau opened the meeting by welcoming me to Lhasa. He then briefed me on Ngawang Sangdrol’s situation. Her parole had been approved by the Lhasa Intermediate Court on October 17, 2002, and her parole was being managed by the local public security office of the district where she lived. Mr. Tsering said she was allowed to travel around Lhasa, and that she had visited monasteries in the area around the city. She was required to report to public security once a month.

I worked with Chinese, American, and Swiss officials in Beijing and with American officials in Washington and Swiss officials in Bern to bring about Ngawang Sangdrol’s safe passage to the United States and Switzerland. Not long after my visit to Lhasa, she was granted medical parole by the warden of Drapchi Prison. (Parole and sentence reductions are approved by courts, medical parole is approved by prison wardens.) She boarded a plane to Beijing and, accompanied by an officer of the American Embassy, flew to the United States, arriving on March 28, 2003. She then went to Switzerland where, with the assistance of the Swiss government and the generous support of the Rossottos, she settled in Rikon, together with Jigme Sangpo in exile. Ngawang Sangdrol eventually settled in the United States.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.