The UN’s adoption of the Bangkok Rules in December 2010 created a new set of standards governing the treatment of women prisoners worldwide, but nearly a year later, implementation is at a standstill in China and other countries. China’s judiciary has shown a general lack of knowledge about the standards; the Ministry of Justice has expressed little interest in engaging with outsiders on the rules, and the Chinese press has hardly mentioned them.

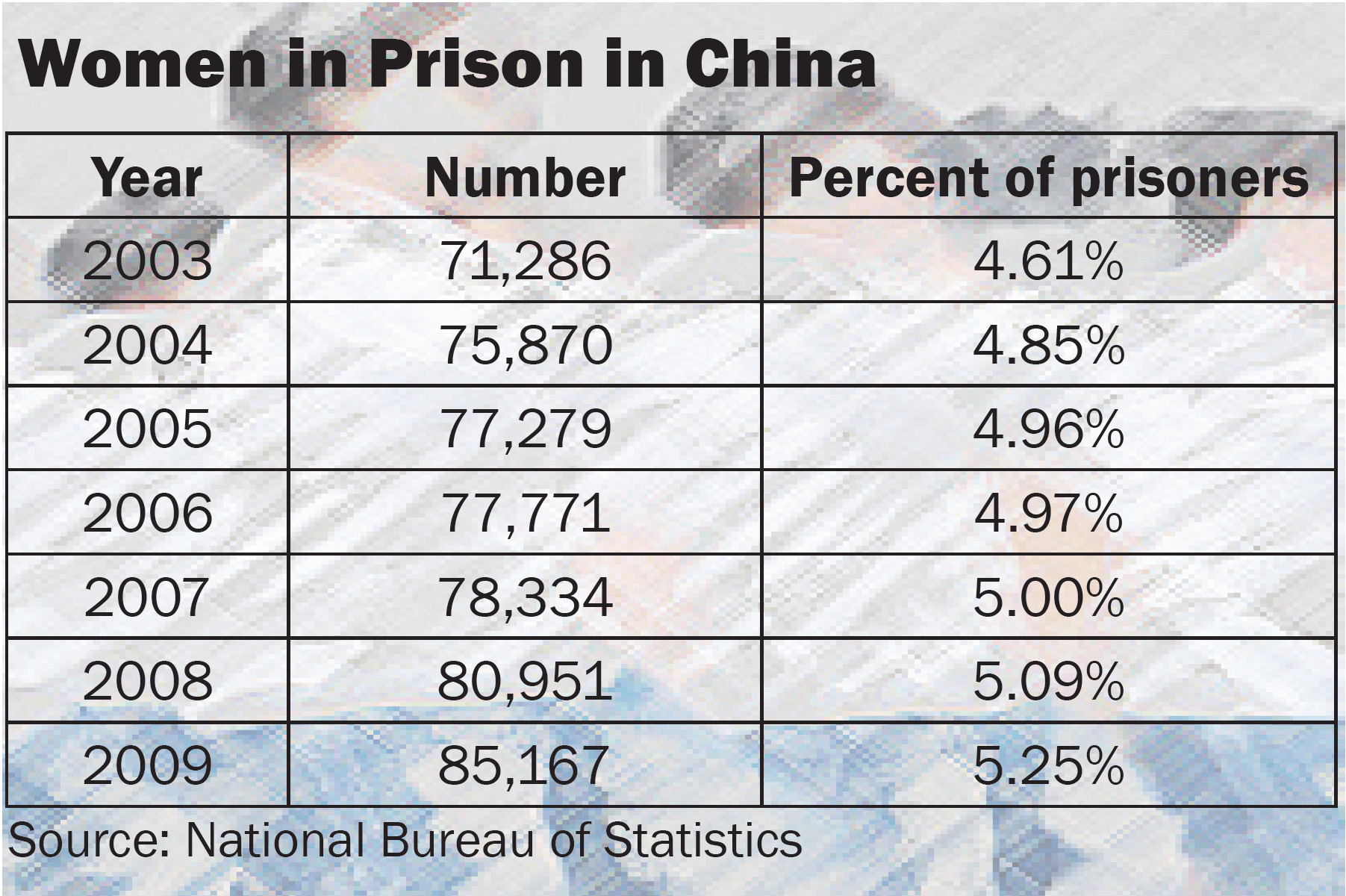

It would seem as though growth in the world’s population of women detainees has not affected China, but since 2003, the country’s population of women prisoners has grown faster than that of men. More than five percent of China’s prisoners were women in 2009, and if the growth rate registered that year is maintained, there will be nearly 100,000 women prisoners in China by mid-2012.

In fact, the low-profile of the Bangkok Rules aside, the rise in the number of women prisoners has led to some progress in the treatment of women in China’s criminal justice system. While national projects have yet to take hold, pockets of change in places like Hunan, Chongqing, and Hebei have addressed areas of concern enumerated in the Bangkok Rules, especially with respect to domestic violence.

National Problem

Rule 67

“Research shall be conducted on the reasons that “trigger women’s confrontation with the criminal justice system.“

Generally, the Bangkok Rules take into account not only the increasing number of women in prison but the “disproportionate experience of domestic violence” shared by women prisoners.

Since 2000 a great deal of research has been done on the triggers of crime committed by women in China. A recent survey conducted by the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF) indicated that domestic violence played a role in more than 50 percent of crimes committed by Chinese women and that domestic violence is the cause of 80 percent of violent crimes committed by women.

Partly the result of advocacy work by the ACWF and findings that domestic abuse occurs in more than a third of Chinese families, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress announced plans to draft an independent anti-domestic violence law in August 2011. In preparation for the national law, a research group traveled to Changsha, the capital of Hunan province, in March to study the implementation of municipal regulations lauded as China’s first anti-domestic violence rules in 1996. As of 2010, similar regulations for handling complaints and defining organizational procedures had spread throughout the nation, with the exception of Guangdong, Tibet, Shanghai, and Beijing.

The Standing Committee has not given a timetable for when a draft of the law will be circulated for public comment or when it might become effective. But media reports have increased awareness about the upcoming legislation. News of the law grabbed popular attention in September 2011 when Li Yang, well-known for his development of a popular English-learning technique, publically apologized for beating his American wife after she posted photos of her injuries on a Chinese microblogging service.

Local Clemency

Rule 56:

“Sentencing alternatives shall be developed within Member States’ legal systems, taking account of the history of victimization of many women offenders.”

Judicial officials and scholars have jointly launched pilot schemes at the local level to examine the use of reduced sentences for women convicted of murdering their abusive husbands. A volume of selected criminal cases published in 2007 shows that courts in various provinces have handed down reduced sentences for women defendants based on past domestic violence, caretaking responsibilities (emphasized in Rule 63 discussed below), and confession. The cases also show precedent for granting suspended sentences to domestic-violence survivors convicted of capital crimes like murder and aggravated assault.

The first provincial guiding opinion on domestic violence was issued by the Hunan High People’s Court in 2009. It encourages courts to grant lighter sentences and sentence reductions to those who “fought violence with violence” (以暴制暴). A year later the vice president of the Chongqing High People’s Court suggested that domestic-violence survivors be exempt from punishment since their crimes were “less heinous.”

But despite progressive locales, China has yet to develop a national sentencing standard, and most women who commit violent crimes as a result of domestic violence receive severe punishment ranging from death with reprieve to 10 years’ imprisonment. As pointed out by an article in China Women’s News (中国妇女报), some local courts justify the use of severe punishment on the grounds that leniency would encourage more women to commit violent crimes at home.

Rule 63:

“Decisions regarding early conditional release (parole) shall favourably take into account women prisoners’ caretaking responsibilities.”

During a Women’s Rights Week event in March 2004, organized in Hebei province by the provincial women’s federation and women’s prisons, 26 women prisoners were granted either sentence reductions or parole. The Shijiazhuang Intermediate People’s Court offered clemency on the grounds that these women suffered chronic physical and psychological trauma inflicted by their husbands, had no prior criminal record, and “fought violence with violence.” While many local regulations make individuals convicted of violent crime ineligible for clemency, regulations issued in Beijing in 2005 made an exception for victims of domestic violence. Under the 2005 rules, these prisoners become eligible for sentence reduction and parole after serving two-thirds of their sentence or one half of their sentence if they show good behavior.

Soft Media, Serious Exchange

Rule 70:

“Raising public awareness, sharing information and training.”

So far public awareness seems to be quite low, with the possible exception of the link between domestic violence and incarceration. This is partly because the bulk of Chinese media reports related to women in prison focus on one-off events like holiday celebrations, beauty pageants, and fashion shows. Contributing to stereotypes of women as soft, trivial creatures, media reports have featured stories on lipstick and makeup privileges, while avoiding serious investigation into more salient topics like sanitation; hygiene; and healthcare, especially as it relates to pregnancy and HIV/AIDS.

China has, however, engaged in international exchanges related to women and domestic violence. Most recently in July 2010, around the time of the plenary session introducing the Bangkok Rules, a seminar on the criminal liability of defendants suffering from battered woman syndrome was hosted in Xi’an by the Shaanxi Women’s Federation, International Bridges to Justice (IBJ), and others. Officials from public security organs, procuratorates, and the Shaanxi women’s prison joined judges, lawyers, and scholars at the event. Adhering to the principle of “combining leniency with punishment,” participating Chinese lawyers proposed fixed-term imprisonment of three to five years for battered women convicted of aggravated assault or murder. Also in attendance, an American lawyer representing IBJ discussed the US practice of referencing expert testimony to present battered woman syndrome as a mitigating circumstance—a procedure not currently used in China.

With involvement from the courts, the National People’s Congress, civil society, and the public, significant progress has been made in the development of research and practices related to domestic violence and its role in the incarceration and sentencing of women in China. Similar cooperation and momentum is necessary to promote the implementation of the Bangkok Rules both nationally and internationally. China has shown that it has as much to teach as it has to learn by engaging in international exchange, and existing precedent shows that meaningful dialogues can and should be held regarding the sentencing and treatment of women detainees.