<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Download & read this story as a PDF.

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan in early August 2022 was praised and criticized in equal measure. It resulted in massive Chinese military drills as well as a surge in foreign delegations to the island. China’s President Xi Jinping asked US President Joe Biden to intervene to stop Pelosi, but Mr. Biden declined to do so. The Biden administration did, however, take steps to discourage the speaker from making the trip.

After Speaker Pelosi’s visit, China canceled or suspended cooperation with the United States on a range of issues, including military talks, climate change, and law enforcement, notably involving narcotics.

Her Taiwan visit was not Mrs. Pelosi’s first foray to Greater China to promote democracy and human rights.

In September 1991, Pelosi and two other members of Congress, Ben Jones and John Miller, traveled to Beijing accompanied by staff and representatives of NGOs, including the AFL-CIO. While there, they slipped out of their hotel, unbeknownst to their host, and went to Tiananmen Square where they unfurled a banner that read “To Those who Died for Democracy in China.” The police quickly moved in, and Pelosi tried to run away in high heels. The Representatives were questioned and let go.

“It was my first experience with Pelosi’s penchant for high-profile gestures designed to poke China’s communist rulers in the eye – regardless of the consequences” wrote Mike Chinoy, CNN’s bureau chief in Beijing. Chinoy, who had not been forewarned of Mrs. Pelosi’s plans, and his cameraman were roughed up by the police and placed under arrest. Journalists from two other networks, ABC and CBC, were similarly treated. Officials at Pelosi’s host organization were punished. American ambassador Stapleton Roy was furious and confronted Pelosi in the lobby of the hotel. Congresswoman Pelosi did not care about any of this. Her mission had been accomplished; her profile had been lifted.

In fact, I am grateful to Congresswoman Pelosi for what she did in Tiananmen Square that day in September 1991. Though she has no idea why I’m grateful, in fact her protest led directly to some of my early successes, including the release of Hong Kong Trade Development Council representative Lo Hoi-sing, son of a senior journalist at a Hong Kong left-wing paper.

Operation Yellow Bird

In the aftermath of the killings in Chinese cities in June 1989, loosely coordinated efforts began to spirit protesters out of China to safe havens outside of the mainland, notably Hong Kong, then a British crown colony. These efforts involved more than 40 people, some of whom were members of triads, others of whom were local Chinese officials. The efforts were dubbed “Operation Yellow Bird 黄雀行动,” and they led to the saving of more than 130 of China’s leading dissident students and intellectuals, including Wu’er Kaixi, Yan Jiaqi, and Su Xiaokang.

These efforts were risky, and some operatives were caught and punished. Lo Hoi-sing (pinyin: Luo Haixing, simple: 罗海星, traditional: 羅海星), a Hong Kong businessman, was detained on October 14, 1989, and formally arrested on December 18 the same year. He was tried with two “co-conspirators,” Hong Kong residents surnamed Li Peicheng (黎沛成) and Li Longqing (李龙庆), on March 4, 1991. After Lo was released, he told me that he didn’t know either Li; he had met them for the first time at trial.

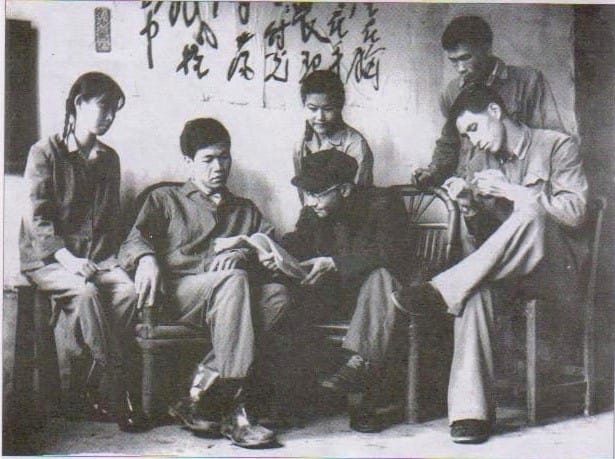

For the crimes of harboring criminals and belonging to a counterrevolutionary group, Lo was sentenced to five years in prison, with three years deprivation of political rights (DPR). Lo was accused of trying to help Chen Ziming and Wang Juntao escape China. He was shipped off to Huaiji Prison in western Guangdong Province. He occupied a cell next to that of Wang Xizhe of “Li Yi Zhe” fame. Li Yi Zhe referred to a group of Guangzhou dissidents who put up posters calling for democracy in the mid-1970s.

Shortly after Lo Hoi-sing’s trial, his wife, Zhou Mimi (Chow Mat-mat), came to see me at my office in Hopewell Center, a high-rise office building in Hong Kong’s Wanchai District. Ms. Zhou, an author of children’s books, asked me to try to secure her husband’s release. I agreed and began putting Lo’s name on prisoner lists submitted to the Chinese government.

Flight to Beijing

On June 10, 1991, I flew to Beijing for a two-day visit. I was determined to seek clemency for Lo Hoi-sing and the Li Brothers (Li Lin and Li Zhi), two young Hunan labor activists who had escaped China after June 4, but who had returned to Hunan where they were detained. On June 11, at 2:00 PM, I met Supreme People’s Court Vice President Lin Zhen and State Council Deputy Secretary General He Chunlin. I had met He a few weeks earlier in Hong Kong. At that meeting I raised the cases of Lo Hoi-sing and the Li Brothers.

I asked Vice President Lin if Lo Hoi-sing could be considered for early release. His response was hopeful: Lo could be considered for early release under certain conditions. I then asked, in English, about Li Peicheng and Li Longing. Vice President Lin misunderstood me and thought I was referring to the Li Brothers. “In accordance with policy, if they have not committed new crimes after returning to China, they will be released from detention,” the vice president intoned. The next month, the Li Brothers arrived in Hong Kong. They were granted political asylum in the United States. It was my first major success.

North-South Strategy

I returned to Beijing in August 1991. By then, I had garnered a great deal of positive media attention that resulted from my AmCham initiatives, my three congressional testimonies, and the release of the Li Brothers. I had been awarded “Communicator of the Year” by the International Association of Business Communicators. I was considered a media “guru.”

In my meetings with Chinese officials, I made a bold prediction. It was already known that Nancy Pelosi would visit Beijing. I predicted that she would do something “that would make the Chinese government unhappy.” Following the principle that the best way to counter bad news is to release good news, I suggested a “North-South Strategy.” To counter bad news in the north, release good news in the south.” I recommended that Hong Kong resident Lo Hoi-sing be released from prison on medical parole and sent back to Hong Kong with as much fanfare as possible. My interlocutors paid attention and took careful notes.

When Nancy Pelosi unfurled her banner on September 4, 1991, the Chinese government acted quickly. A call was made to the Guangdong government which ordered the immediate release of Lo Hoi-sing. A car was sent to Huaiji Prison from Guangzhou to pick up Lo, but the officers forgot to take Lo’s travel documents with them. The car returned to Huaji before going back to Guangzhou, but Lo Hoi-sing’s release had to be delayed.

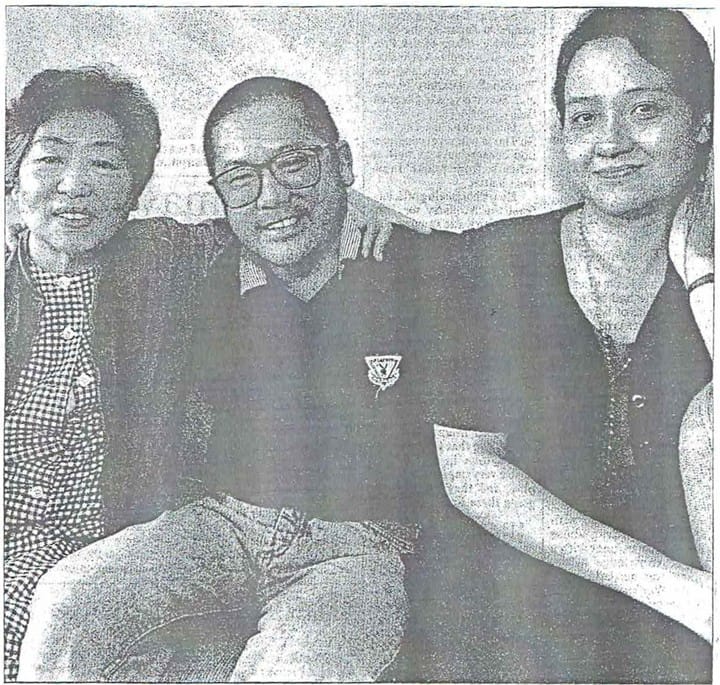

Lo was granted medical parole and he arrived in Hong Kong on September 9, 1991, met with banner headlines and photographs of beaming family members reunited with their loved one. Lo never served his DPR sentence.

British Prime Minister John Major had been in Beijing at the same time as Nancy Pelosi. He flew to Hong Kong’s Kai Tak Airport where he learned of Lo’s release. He immediately set about claiming credit, advancing the preposterous notion that Beijing was grateful for the prime minister being the first Western leader to visit China’s capital since the events of June 1989. I said nothing to contradict Major’s claims, relying on an adage that Ronald Reagan was fond of: “There is no limit to what a man can achieve if he doesn’t care who gets credit for it.”

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.