After delays caused in large part by the scandal involving disgraced Chongqing Party Secretary Bo Xilai, the 18th Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) will convene in Beijing on November 8. A new leadership will be announced at the end of the congress, including that of China’s paramount political body, the Standing Committee of the Politburo, whose membership is likely to be reduced to seven from nine. This downsizing could have important consequences for human rights and rule of law in China as it would likely eliminate the seat currently occupied by the chairman of the Central Politico-Legal Committee (PLC). The PLC is responsible for “stability maintenance” (weiwen) and oversight of the public security and state security apparatuses, procuratorates, and the Ministry of Justice. If the seat held by the PLC chief is eliminated, it could signal a de-emphasis on the current policy of “stability above all else,” which has been used to trample dissent.

Politburo Standing Committee members elected at the 17th party congress in 2007. Photo credit: Xinhua |

Although the full line-up will not be certain until it’s announced, it is virtually certain that Xi Jinping will be named as the next party secretary (replacing Hu Jintao), and that Li Keqiang will assume the number two position (replacing Wen Jiabao). If this occurs, these two men are also expected to assume the respective positions of president and premier in March 2013.

Others who may be elected to the Politburo Standing Committee include: CPC Organization Department head Li Yuanchao, the former party secretary of Jiangsu Province; Vice-Premier Wang Qishan, who is in charge of economics and trade policy; Chongqing Party Secretary Zhang Dejiang, Bo Xilai’s replacement; Tianjin Party Secretary Zhang Gaoli; Guangdong Party Secretary Wang Yang; and Shanghai Party Secretary Yu Zhengsheng.

Whoever makes the cut, the body will face a host of serious challenges. China’s economy is slowing, with manufacturing, exports, and imports all exhibiting weakness. The country is embroiled in territorial disputes with its neighbors—most ominously with Japan, its largest trading partner—that highlight the increasing influence of China’s assertive military. Social unrest is also rising, as are calls for political reform. State Counselor Niu Wenyuan said there were an average of 500 “mass incidents” every day in 2011, and the number has shown no sign of abating. The numbers of arrests and prosecutions for endangering state security also remain high. On top of these challenges, the new leadership will have to deal with the outcome of the US presidential election taking place just two days before the party congress convenes.

Human rights is where these issues intersect and looking at the records of Standing Committee candidates may indicate the direction of traffic. Set to become the first party secretary not to have been blessed by either Mao Zedong or Deng Xiaoping, and the youngest party secretary to assume power since Hua Guofeng in 1976, Xi Jinping is more likely to rule by consensus than fiat. Understanding the human rights footprint of Xi and those who may, or may not, join him on the new Standing Committee can help chart the future development of human rights in China.

Xi Jinping: A Pragmatic Conservative

Prior to moving to Beijing to take up the position of vice-president and Standing Committee member, Xi Jinping served as deputy party secretary in Fujian Province (1995–2002) and party secretary in Zhejiang Province (2002–2007). He gained a reputation for targeting independent trade unions in Fujian and underground house churches in Zhejiang. Yet, while he was Zhejiang party secretary, he readily approved the release on medical parole of Wang Youcai (王有才), co-founder of the China Democracy Party, in March 2004.

In Fujian, Xi oversaw the April 2002 arrests of Li Jianfeng (李建峰) and seven other activists who formed an independent trade union. All received stiff sentences, with Li sent to prison for 16 years. After Xi departed from Fujian for Zhejiang, those imprisoned in the case began to be granted clemency. As of early last year (when Dui Hua was last updated), all but Li Jianfeng had been released. After receiving sentence reductions totaling 38 months, Li will not be free until February 2, 2015.

Mass Incidents Handled in Zhejiang under Party Secretary Xi Jinping | ||||

Type | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 |

Petitioning | 654 | 609 | 521 | 352 |

Illegal assembly, parade, demonstration | 18 | 16 | 33 | |

Surrounding, attacking party or government buildings | 148 | 82 | 79 | |

Disrupting traffic | 126 | 138 | 92 | 65 |

Mass fighting with weapons | 81 | 37 | 24 | |

Obstructing performance of official business | 131 | 97 | 40 | |

Causing serious disturbances, riots | 189 | 133 | 115 | |

Smashing, looting, burning | 21 | 10 | 4 | |

Total | 1,739 | 2,950 | 2,211 | 1,658 |

Source: Compiled from annual editions of Zhejiang Province Public Security Records. | ||||

During Xi’s tenure as party secretary, Zhejiang imprisoned more members of the China Democracy Party—one of the largest underground opposition parties to develop in China after the founding of the People’s Republic—than any other province, according to Dui Hua’s Political Prisoner Database (PPDB). But in the wake of 9/11, then Party Secretary Jiang Zemin adopted a strategy of freeing political prisoners to court warmer relations with Washington. Regional party secretaries were asked to support the strategy and facilitate releases. Xi readily agreed to release Wang Youcai. Others were less agreeable. Xinjiang Party Secretary Wang Lequan strongly resisted the release of business woman and Uyghur rights activist Rebiya Kadeer during 2004 and 2005. Wang didn’t concede until he received a direct order from Jiang’s successor, Hu Jintao.

Under Xi’s reign, 2005 marked the “first time in recent years” that police were transferred between cities in order to quell mass incidents, according to provincial public security yearbooks. The number of mass incidents declined in 2006 and 2007 (see table).

After Xi’s arrival in Beijing, he teamed up with Standing Committee member and PLC chief Zhou Yongkang to establish a stability maintenance office to silence dissidents around sensitive anniversaries like National Day or June 4. Although Xi is seen as a supporter of growth and pro-economic reform, he has little patience for critics of China’s human rights record. He has deemed international actors as “foreigners, with full bellies, who have nothing better to do.” He has also shown no interest for political reform in China or democracy in Hong Kong. Observers believe that as head of the Central Committee’s Hong Kong-Macao Affairs Leading Small Group, Xi instructed China’s Hong Kong-based representatives to lobby for the election of C. Y. Leung as Hong Kong’s chief executive. This would have violated the spirit, if not the letter, of Hong Kong’s Basic Law, which guarantees self-governance.

Li Keqiang: Strict Enforcer of “Stability”

Li Keqiang became deputy party secretary of central China’s Henan Province—sometimes called China’s Bible belt for its high concentration of evangelical Christians—in June 1998 and rose to become party secretary in December 2002. After serving two years as Henan party secretary, he was transferred to Liaoning Province in China’s heavily industrialized northeast—home to a large population of Falun Gong practitioners—where he served as party secretary (December 2004–October 2007) before relocating to Beijing to serve on the Politburo Standing Committee.

Li Keqiang became deputy party secretary of central China’s Henan Province—sometimes called China’s Bible belt for its high concentration of evangelical Christians—in June 1998 and rose to become party secretary in December 2002. After serving two years as Henan party secretary, he was transferred to Liaoning Province in China’s heavily industrialized northeast—home to a large population of Falun Gong practitioners—where he served as party secretary (December 2004–October 2007) before relocating to Beijing to serve on the Politburo Standing Committee.

During his time in Henan, villagers who sold blood to government-run blood banks were infected by AIDS, and thousands perished. In some “AIDS villages,” the entire adult population was decimated. Li has been criticized for trying to cover up the blood-trade scandal, failing to hold government officials accountable, and overseeing the harassment and house arrest of whistle-blowers like Dr. Gao Yaojie (高耀洁) and Wan Yanhai (万延海), both of whom have fled to the United States.

In Liaoning, Li is said to have suppressed media coverage of devastating fires and strikes at state-owned enterprises. In an unrelated case, poet and journalist Zheng Yichun (郑贻春) was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment by the Yingkou Intermediate People’s Court for his pro-democracy writing. He was released last December after completing his full sentence.

Drawn largely from workers whose livelihood was squelched by the shuttering of state-owned enterprises, Liaoning has one of the highest populations of Falun Gong practitioners in China. Dui Hua’s PPDB includes the records of 284 Falun Gong practitioners sentenced in Liaoning during Li’s term as provincial party secretary. Evidence suggests that Falun Gong was not the only religious movement targeted. In November 2006 seven followers of Zhonggong—or the “China Healthcare and Wisdom Enhancement Practice,” a sect banned in same year as the Falun Gong—were detained and given long prison sentences, some of which remain on-going.

Li Yuanchao: A Cautious Reformer

Of all of the candidates in the running, Li Yuanchao has exhibited the greatest tolerance for dissent as well as a measure of sympathy for political prisoners.This has been held against him in the past and could well affect his chances to join the Standing Committee. If he is elected, he will likely advocate for political reform within the confines of one-party rule.

In 1991, Li was appointed deputy director of the State Council Information Office. The tragic events of June 4, 1989, were still very much on the mind of the international community, and Li saw the value of releasing protesters and other political prisoners from the Democracy Wall era. (In his position as a senior member of the Communist Youth League in the late 1980s, Li authorized the publication of articles supportive of the student protests, causing him to temporarily fall out of favor.) Working with American businessman John Kamm (now executive director of Dui Hua), Li helped publicize the releases of scores of prisoners.

Li was given mid-career training at Harvard Kennedy School in the early 2000s. Speaking at the school in 2009, he credited this training with his ability to maintain transparency during a Nanjing food poisoning crisis.

During his tenure as party secretary of Jiangsu (2002–2007), Li earned a reputation for being tough on corruption. He also became known for his concern for the environment and ordered the closure of thousands of chemical plants that were polluting the province’s many scenic places, including Taihu Lake. Unlike Xi Jinping, he took a soft approach to handling mass incidents, and very few dissidents were arrested and prosecuted during his tenure, according to the PPDB.

In his current post as Organization Department chief, Li is known for his opposition to Bo Xilai’s attempt to revive Maoism. Immediately after Bo was deposed, Li addressed the assembled cadres and told them that Bo’s reign—during which many human rights abuses were committed in the name of “strike black” campaigns against organized crime—was over. ■

Polls: Americans Prioritize Human Rights in China

To an extent not seen in previous US presidential campaigns, how to deal with a rising China has been a major issue in the 2012 contest. Romney has repeatedly said he’d name China a “currency manipulator” the day he takes office and otherwise crack down on Chinese “cheating.” Obama has showcased the actions he’s taken against Chinese imports and has accused his opponent of investing in Chinese companies and shipping American jobs to China.

American public opinion polls seem to have been fueling attempts to appear tough on China. In 2012 alone there were at least three polls showing double-digit drops in China’s favorability ratings. The polls reveal deep concern over China’s growing economic and military might, but none of them explicitly examine American attitudes towards China’s human rights record.

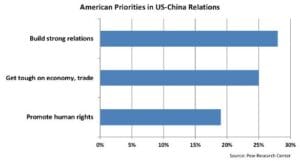

In September 2012, however, the Pew Global Attitudes Project conducted a poll of American attitudes asking specifically about human rights in China. Querying how important promoting human rights was for US policy towards China, 53 percent of the general public said that it was “very important,” while an additional 28 percent called it “somewhat important.” Choosing between the very important issues they identified, 19 percent of respondents selected promoting human rights as “most important.” This was the third most popular selection, lagging nine points behind the leader, “build[ing] a strong relationship with China,” and six points behind “be[ing] tough” on economic and trade issues.

In January 2011, 40 percent of Americans thought that it was very important to “do more to promote human rights in China,” while 32 percent thought it was somewhat important, according to a Pew Research Center poll. Consistent with this later finding, a CNN/Opinion Research Corporation poll found in February 2010 that Americans felt taking “a strong stand on human rights in China” (53 percent) was more important than maintaining “good relations with China” (44 percent). American disapproval of China’s human rights situation was summed up by the same polling organization in November 2009: 68 percent of Americans gave the Chinese government “mostly bad” or “very bad” marks for “respecting the human rights of its citizens.”

Despite economic concerns, promoting human rights remains among the top priorities that Americans identify for the US government’s foreign policy initiatives towards China. How the winner of the 2012 presidential election manages the public’s expectations is likely to be one of the biggest challenges of US-China relations over the next four years. ■